In the landscape of modern corporate governance, a crisis is not a matter of “if” but “when.” A product recall, an ethical lapse, or a data breach can erase billions in market value within hours. While the event itself is often uncontrollable, the leadership response is not. New research demonstrates that the financial outcome of a crisis, measured in stock performance, is critically dependent on the linguistic choices made in the public apology.

The thesis, supported by research from academics including Prachi Gala, is that a single word choice by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) functions as a powerful, quantifiable financial signal to investors.

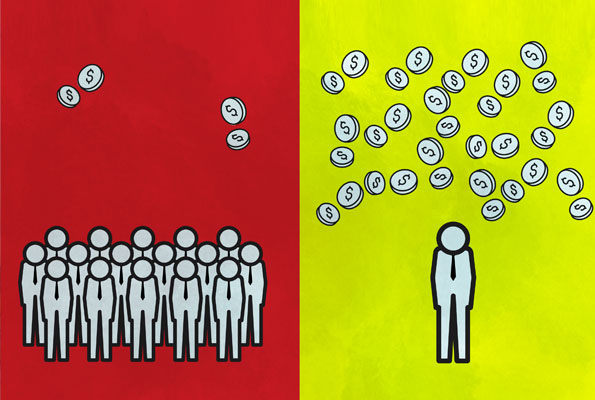

The CEOs who frame their apologies using the singular pronoun, for example, “I apologise,” experience significantly smaller stock price drops. In some cases, this acceptance of personal responsibility can even be correlated with modest stock gains in the immediate aftermath. Conversely, CEOs who employ the collective pronoun, for example, “we apologise,” are associated with the very stock sell-offs they are attempting to prevent.

This finding reframes the act of a corporate apology. It is not a “soft” function of public relations or a matter of rhetorical style. Instead, it is a hard, financially material action. The linguistic framing of the apology is a direct signal to the market, and investors, who are the primary audience for this type of financial research, have learnt to decode it.

The market’s positive reception to “I” is based on its perception as a direct signal of personal accountability. When a CEO uses the singular pronoun, they are communicating strong, decisive leadership.

They are, in effect, telling the market that the problem has been identified, that a single, high-ranking individual is taking ownership, and that the chain of command is intact. This perception of control and accountability is precisely what investors seek in a moment of high uncertainty.

Conversely, the use of “we” is perceived by the same investors as evasive. This collective pronoun is interpreted as a deliberate attempt to spread, or diffuse, responsibility so thinly that no single individual can be held accountable.

This linguistic choice triggers a cascade of negative assumptions. Assumptions that the leadership is weak, that the CEO is unaware of where the fault truly lies, or, perhaps most damagingly, that the CEO is aware and is actively concealing the single point of failure.

This leads to what can be termed an “evasion penalty.” The negative stock performance following a “we” apology is not merely a failure to create a positive outcome; it is an active financial punishment for the perceived evasion. Investors penalise the “we” apology because it suggests a lack of control and a high risk of future, unmanaged failures.

Financial methodology of apology

To assert that a single pronoun can impact a firm’s stock price requires a rigorous, quantitative methodology. This claim rests on the “event study method,” a standard and widely accepted tool in financial economics used to measure the impact of a specific event on the value of a firm.

This method allows analysts to isolate the financial impact of a specific announcement, such as a crisis apology, from the market’s general fluctuations. The process, in simple terms, involves three steps.

An “estimation window” (for example, 200 days before the event) is used to observe the stock’s normal performance relative to the market, establishing an expected return. Analysts define a short “event window” (for example, the day of the apology and the few days surrounding it) to measure the stock’s actual performance.

The core output is the Cumulative Abnormal Return (CAR), which is the difference between the stock’s expected performance (from the baseline) and its actual performance during the event window.

This methodology is specifically designed to demonstrate the short-term impact of crises, such as product-harm incidents, on a firm’s financial value. It is the tool that allows analysts to move from correlation to a strong inference of causation, isolating the market’s reaction to the event itself.

Psychology of diffusion

Under “diffusion of responsibility,” individuals in a group feel less personal accountability for taking action (or for a failure) because the presence of others dilutes their sense of responsibility. It is the “someone else will handle it” effect.

Research highlights that diffusion of responsibility is most common in “hierarchical organisations” and “group decision-making processes,” which perfectly describes the modern corporation.

The very mechanisms of corporate efficiency, such as “division of labour” and “collective action”, create this diffusion. They allow individuals to shift their attention from the “morality of what they are doing to the operational details” of their specific job, creating a psychological schism between causal influence and moral accountability.

When a CEO, the highest-status individual at the apex of this hierarchical organisation, issues an apology beginning with “we,” they are doing far more than making a grammatical choice. They are linguistically triggering the market’s deepest fears about corporate structures.

The “we” apology is a verbal confirmation of the diffusion of responsibility. It tells stakeholders that the organisational structure itself (the “we”) is to blame, and that this same structure is now being used to obscure accountability. It creates profound ambiguity and leads to a situation often referred to by researchers as responsibility gap. A harm has occurred, but there is no identifiable, culpable agent.

Investors, who abhor ambiguity and unmanaged risk, interpret this “we” not as collective remorse but as a definitive statement that no one is in control and no one will be held personally accountable. This signals a systemic, unmanaged, and potentially recurring risk, which is a clear signal to sell.

The ‘I/We’ contradiction

Prominent business thinkers, like Reid Hoffman, explicitly train leaders that “‘I’ vs ‘We’ is a false choice. It’s both,” promoting a collaborative team-building concept of “I We.” This “people-centric” approach is excellent for internal management, for sharing credit, and for building a cohesive team.

Furthermore, in a scandal, employees themselves may begin to create an “I vs We” separation to distance their personal identity from the corporate misconduct. This creates an internal environment where a “we” apology from the top feels hollow.

This creates a “trained (wrong) reflex.” The CEO’s entire career has been built on the collaborative, inclusive “we.” Then, in the moment of crisis, this instinct is powerfully reinforced by the two departments they trust most, the legal and human resources departments.

Therefore, when a “preventable crisis” hits, the CEO’s entire support system (legal, HR, and their own well-honed leadership instincts) will be screaming, “Say ‘we’!” What Prachi Gala’s report provides is the financial and psychological evidence that this instinct, while logical and well-intentioned, is strategically catastrophic and financially damaging in this specific, external-facing context.