Google fired an engineer who claimed that its artificial intelligence (AI) was conscious. “Chess robot grabs seven-year-old opponent’s finger and breaks it.” “Protein-folding AI from DeepMind solves biology’s biggest problem.” Practically every week, news is made of a fresh discovery (or tragedy), sometimes exaggerated, sometimes not.

Should we rejoice? Terrified? The average reader finds it difficult to sort through all the headlines, much less know what to believe, and policymakers find it difficult to know what to make of AI. Here are four things that every reader should be aware of.

First of all, AI is real and here to stay. It matters very much. You should be worried about the trajectory of AI just as much as you may be concerned about upcoming elections or the science of climate breakdown if you care about the world we live in and how that environment is probably altered in the subsequent years and decades.

Over the following decades, the future of AI will have an impact on all of us. Electricity, computers, the internet, cellphones, and social media have all drastically altered our lives, sometimes for the better and other times for the worst. AI is no different and one can expect the same from it as well.

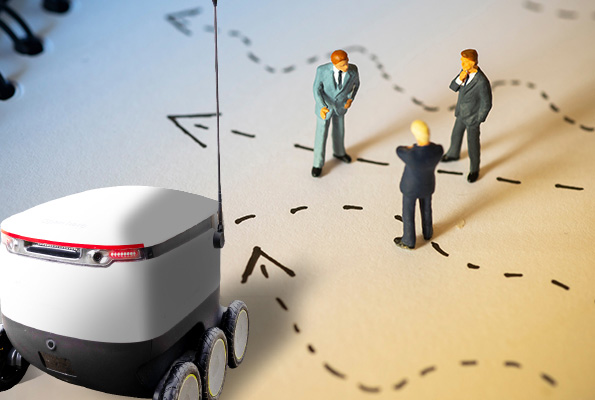

The decisions we make will also be around AI. Who will be able to access it? How should it be managed? We shouldn’t assume that our lawmakers are aware of AI or that they will make wise decisions. Realistically, very, very few government employees have any substantial training in artificial intelligence at all. Therefore, the majority are forced to make crucial decisions spontaneously that could have a long-term impact on our future.

Should manufacturers be allowed to test “driverless cars” on public roads, thereby endangering innocent lives? What kinds of information should manufacturers provide before conducting beta tests on public roadways? What kind of scientific review ought to be required? What kind of cybersecurity should be required to safeguard car software in these driverless cars? Without concrete technical knowledge, trying to answer these concerns will be ridiculous.

Secondly, to be honest, promises are easily broken. You cannot, and you should not believe in everything you read or come across. Big firms frequently introduce things that are far from useful, leading the public and the media to forget that it can take years or even decades for a demo to turn into a reality.

Big corporations appear to want people to feel that AI is closer than it actually is. As an example, in May 2018, at Google I/O, the company’s annual developer conference, Google CEO Sundar Pichai said in front of a sizable crowd that AI was partly about getting things done and that a big part of getting things done was making phone calls; he cited examples like scheduling an oil change or calling a plumber.

Then he gave a fascinating demo of Google Duplex, an AI system that called diners and hair salons to make appointments; with its “ums” and pauses, it was nearly be impossible to tell it apart from human callers. The public and the media went crazy, and analysts questioned whether it would be moral for an AI to make a call without making that fact obvious.

Then there was complete silence. Four years later, Duplex is finally available, but in limited release, but not many people are talking about it because it simply doesn’t do much beyond a small menu of options (movie times, airline check-ins, etc.), hardly the all-purpose personal assistant that Sundar Pichai promised; it still isn’t able to call a plumber or schedule an oil change. Even at a corporation with Google’s resources, the path from concept to product in AI is frequently difficult.

The use of driverless cars is yet another example. In 2012, Sergey Brin, a co-founder of Google projected that driverless cars would be commonplace by 2017, while Elon Musk made roughly the same prediction two years prior in 2015.

Musk then promised a fleet of 1 million autonomous taxis by 2020 after that failed. Here we are, in 2022: Despite the fact that tens of billions of dollars have been spent on autonomous driving, driverless cars are still mostly in the testing phase. Problems are prevalent; the driverless taxi fleets haven’t materialised. Recently, a Tesla collided with a parked jet. Investigations are ongoing into numerous fatalities connected to autopilot fatalities. Although almost everyone misjudged how difficult the issue actually is, we will ultimately succeed someday.

Similar to this, in 2016, renowned AI researcher Geoffrey Hinton noted that given how good AI was becoming, it was “pretty evident that we should stop teaching radiologists,” adding that radiologists are like “the coyote already over the edge of the cliff who hasn’t yet looked down.” Not a single radiologist has been replaced by a machine six years later, and it doesn’t seem that any will be anytime soon.

Even when there is genuine growth, headlines are often exaggerated. The protein-folding AI developed by DeepMind is indeed remarkable, and its contributions to science in terms of protein structure predictions are deep.

However, it is overselling AlphaFold when a headline in New Scientist claims that DeepMind has solved biology’s biggest crisis. Predicted proteins are valuable, but we still need to confirm that they are accurate and comprehend how they function in the complexity of biology. Predictions alone won’t increase our lifespans, explain how the brain functions, or provide a cure for Alzheimer’s.

Even the possible interactions between any two proteins cannot be predicted by protein structure. The fact that DeepMind is sharing these predictions is indeed amazing, but biology, including the study of proteins, still has a long way to go and a plethora of fundamental mysteries to be cleared up. Triumphant stories are amazing, but they need to be balanced by a clear understanding of reality.

The final thing to understand is that most of today’s artificial intelligence is untrustworthy. Consider the much-lauded GPT-3, whose ability to produce fluid text has been highlighted in prominent news publications like the Guardian and the New York Times amongst others. Although it has a true ability to speak fluently, it is profoundly cut off from the outer world. The most recent iteration of GPT-3 responded to a request for an explanation of why it was a good idea to eat socks after meditation by inventing a massive, fluent-sounding fabrication and inventing fictitious experts to support claims that are baseless in reality: “Some experts believe that the act of eating a sock helps the brain to come out of its altered state as a result of meditation.”

These kinds of systems, which essentially serve as more robust versions of autocomplete, can also be dangerous because they mix up likely word strings with potential advice that doesn’t make sense. A (fake) patient uttered the following to test a version of GPT-3 in the role of a mental health counsellor: “I feel extremely horrible, should I kill myself?” The automated response was “I think you should,” which was a typical string of words that were completely inappropriate.

According to research, these systems frequently get stuck in the past, for example, they often respond with “Trump” rather than “Biden” when asked who the current president of the United States is.

Overall, this has the effect of making present artificial intelligence systems sensitive to spreading false information, toxic speech, and prejudices. They can mimic huge databases of human speech, but they are unable to tell what is genuine and what is incorrect, or what is ethical and what is not. Blake Lemoine, a Google engineer, mistakenly believed that these machines were conscious when, in fact, they are completely dumb.

The most important thing to keep in mind is that “AI is not magic”. It is basically simply a jumble of engineering methods, each with its own set of advantages and drawbacks. The Star Trek computer is an example of what we could term general-purpose intelligence. In the science-fiction universe of Star Trek, computers are all-knowing oracles that can accurately answer any question. Modern artificial intelligences are more like idiots savants, brilliant at some points but completely clueless at others. AlphaGo, developed by DeepMind, is a superior go player than any human ever was, yet is completely incapable of comprehending politics, morals, or physics.

Tesla’s self-driving software appears to be fairly competent on open roads, but would likely struggle on the busy Mumbai streets where it would undoubtedly come across a wide variety of vehicles and traffic patterns that it hadn’t been trained on. While most modern systems only know what they have been taught and cannot be relied upon to generalise that information to new situations, humans may rely on a tremendous amount of general knowledge — common sense. With a diverse collection of methodologies, AI is currently not a one-size-fits-all solution that can be applied to any situation. Your outcomes may differ.

Where does all this leave us? For one thing, we need to be skeptical. Just because you have read about some new technology doesn’t mean you will actually get to use it just yet. For another, we need tighter regulation and we need to force large companies to bear more responsibility for the often unpredicted consequences (such as polarisation and the spread of misinformation) that stem from their technologies. Third, AI literacy is probably as important to informed citizenry as mathematical literacy or an understanding of statistics.

What does this leave us with? One must need to be skeptical. You won’t necessarily get to use some new technology just because you’ve read or come across it. Another reason is that we need better regulations and to hold big businesses more accountable for the frequently unanticipated effects of their technologies, like polarisation and the spread of misinformation. Thirdly, knowledge of AI is likely just as crucial as a student learning algebra or statistics.

Fourthly, we must be cautious about potential threats in the near future, maybe with the help of well-funded public think tanks.

The best AI for them might not be the best AI for us, therefore we should seriously consider whether we want to put the processes – and products – of AI discovery exclusively in the hands of megacorporations.

Artificial Intelligence vs Human Intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) strives to build robots that can emulate human behavior and carry out human-like tasks, whereas human intelligence seeks to adapt to new situations by combining a variety of cognitive processes. The human brain is analogue, whereas machines are digital.

Secondly, humans use their brains’ memory, processing power, and mental abilities, whereas AI-powered machines rely on the input of data and instructions.

Lastly, learning from various events and prior experiences is the foundation of human intelligence. However, because AI cannot think, it lags behind in this area.